India Formal, Informal

Latest tax numbers and an expanding digital footprint suggest that the formalisation of the Indian economy is gathering momentum. EPISODE #137

Dear Reader,

A very Happy Monday to you.

Last week the government disclosed that the number of people filing tax returns was poised to touch a new high. According to Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman the number of ITRs filed till 31 July was 7.4 crore. Given that returns can be filed till 31 December, this number would only grow.

Tag this with the surge in the number of tax payers in the Goods and Services Tax (GST) regime and you have a trend: India’s tax base is growing, albeit slowly.

There is a very important subtext: Together with the rapid expansion of the digital footprint of 1 billion Indians, this reflects growing formalisation of the Indian economy. So, this week I explore this phenomenon. Do read and share your valuable feedback.

The cover picture this week is of a road side tea-vendor displaying his e-wallet outside the Talkatora Stadium, New Delhi. A grassroots example of formalisation.

A big shoutout to Niranjan, Rajit, Debu, Lakshmisha, Atul, Gautam, Balesh, Monica, Aashish, Vandana and Premasundaran for your informed responses, kind appreciation and amplification of last week’s column. The piece clearly touched a chord. Once again, grateful for the conversation initiated by all you readers. Gratitude also to all those who responded on Twitter and Linkedin.

Unfortunately, Twitter has disabled amplification of Substack links and content—perils of social media monopolies operating in a walled garden framework. I would be grateful therefore if you could spread the word. Nothing to beat the word of mouth.

Reader participation and amplification is key to growing this newsletter community. And, many thanks to readers who hit the like button😊.

Formalising India

Last week the deadline for filing Income Tax Returns (ITRs) for salaried tax payers and other non-tax audit cases ended. Data released by the Income Tax department soon after, signalled that 6.77 crore people had filed their returns—a record high.

A few days later, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman updated this number. According to her, the ITRs filed till 31 July was higher at 7.4 crore. Given that returns, on the payment of a late fee, can be filed till 31 December, it means this number is likely to be higher.

The tax base—reflecting the surge in the country’s gross domestic product—has almost doubled from the level of 3.8 crore ITRs in 2013-14. This increase in the direct tax base is not an isolated instance.

It plays out in the case of indirect taxes too.

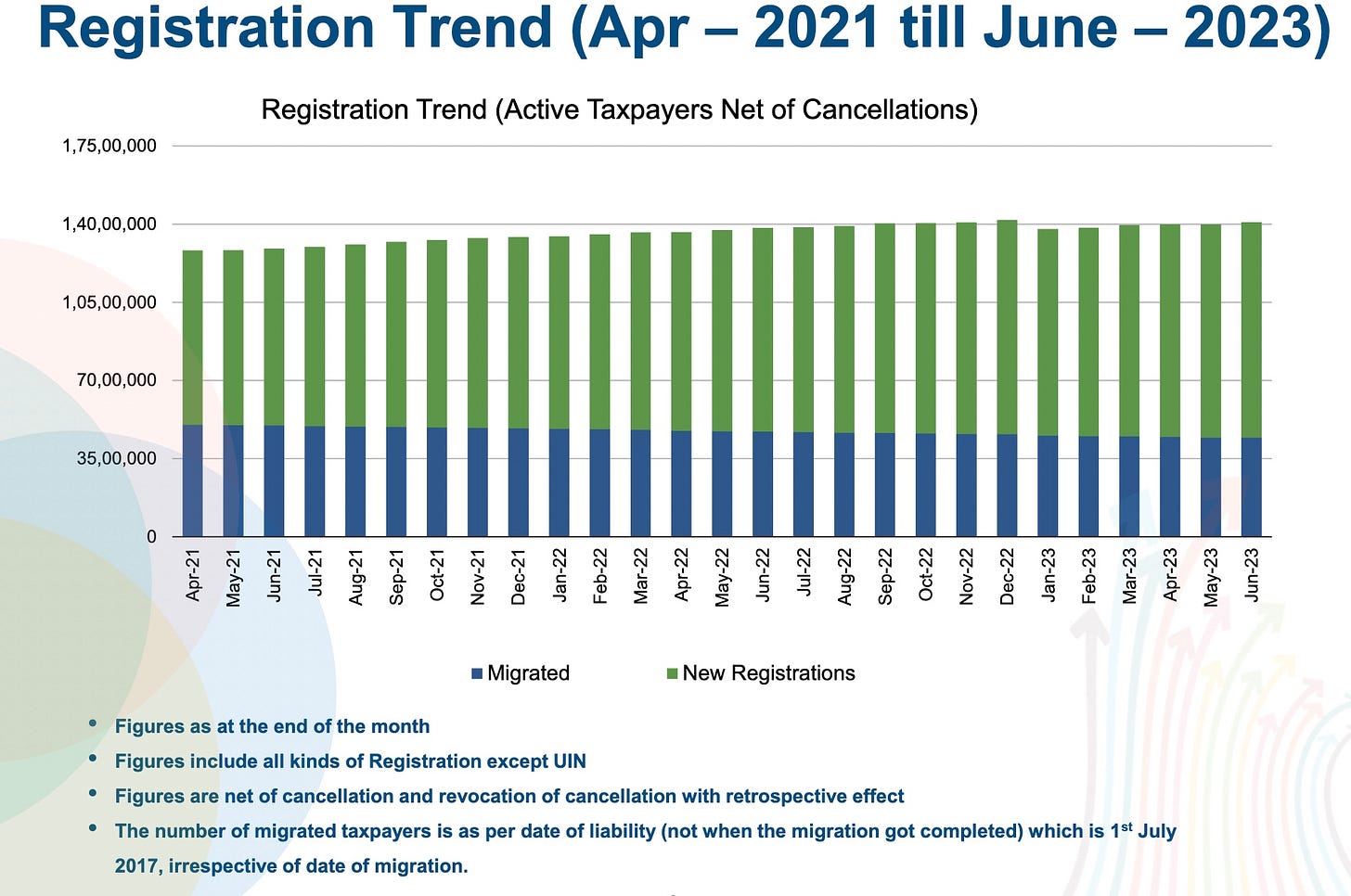

Ever since the launch of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) on 1 July 2017—the marquee tax reform that for the first time economically unified the country—the number of tax payers has grown steadily. The number of tax payers, more than doubled from 60 lakh to 141 lakh on 1 July 2023.

Impressive while these numbers are, together they tell a very important story about New India: It is one of steady formalisation of the Indian economy; the attendant gains from which will be dramatic for both the country as well as its citizens.

Tax Returns

The graphic above captures the growth of the base for direct taxes. To be sure, everyone who files an ITR is not necessarily paying income tax. For instance, in the case of ITRs filed for 2022-23, the income tax department reports that 5.16 crore reported zero tax liability.

Clearly, the structural shift begins from 2016-17—when the union government started wielding the stick on errant tax payers and tax evaders, including the demonetisation of high-value currencies—and accelerates after the roll out of GST—where audit trails shined the light on those who had been evading direct taxes.

The trend for GST tax base is no different. In fact, the growth is actually more dramatic. As mentioned earlier, it has more than doubled in the six years since the launch of the GST.

Keep in mind that while the audit trails of digital transactions are used by tax sleuths to nab the errant among us (and, something that gets all the headlines), there is another equally important takeaway: This digital footprint provides crucial data about an individual/firm that can be harvested for economic advantage—availing credit for example.

The Digital Footprint

If India’s evolving tax system is providing an impetus to formalisation, then its digital economy is not only greasing the economy, but it is also accelerating formalisation. Taking more people out of the informal economy.

And, why is this so important you may ask: It makes more Indians stakeholders in the country’s economy. From being invisible they are transforming into visible economic entities. A win-win situation.

In other words there are fewer among us today who are outside looking in. Not only, does this potentially improve the lot of those who have joined the formal economy, they remain invested in growing the Indian economy.

The rollout of Aadhaar in 2010, set the ball rolling for this profound socio-economic makeover. It resolved the challenge of identity, which was basically a barrier for access to everything: from basics like a ration card to acquiring a bank account or a passport.

What Aadhaar did was to spawn the Digital Public Infrastructure driven by the India Stack—interoperable digital building blocks which solved for identity and payments in a transparent manner. Essentially, it provided a digital platform, on which anyone, private or public, could create innovations—like Unified Payments Interface (UPI)—to create solutions at unimaginable scale.

Effectively, this digital infrastructure has democratised access in an unprecedented manner, bringing more people into the realm of the formal economy and availing its attendant benefits.

Democratising Access

The outcomes of India’s experiment with digital public goods (DPGs) has been dramatic.

Aadhaar paved the way for eKYC, because of which 430 million received a bank account in 10 years—achieving something that could not be managed in the first 70 years since Independence. Linked to their mobile and Aadhaar, this doubled up as an economic GPS to receive targeted social welfare spending through Direct Benefits Transfers (DBT).

So far the union government has brought 312 schemes under the ambit of DBT and have cumulatively transferred a staggering Rs 30.72 lakh crore to beneficiaries. The economic GPS has enabled targeting, resulting in the near elimination of leakages—cumulatively saving the national exchequer Rs 2.75 lakh crore.

The DPGs also enabled the UPI—India’s unique digital payment gateway that took digital transactions to the people. The cover photo of the vendor in this week’s newsletter is a great example of how change has reached the grassroots.

In July, UPI transactions just stopped short of the staggering record of 10 billion transaction—difficult to imagine that seven years ago UPI did not exist. Significantly, more than three-quarters of these transactions were for sums of less than Rs500.

What this proliferation of the digital economy has done is to create a massive digital highway—which is populated transactions undertaken by 1 billion Indians. Indeed, this is nothing then but a valuable digital database that could be leveraged for public good.

The Account Aggregator (AA) framework launched nearly three years ago allows for using this data, based on consent of the owner, to access credit for example. It is a versatile framework that can be deployed for leveraging one’s digital footprint for any use—including health records. (I wrote about this when it was launched. If you wish to re-read it please click this link.)

In the final analysis two things are clear:

One, the formalisation of the Indian economy has grown.

An analyst report issued by the State Bank of India reveals that growth of various channels listed above led to the expansion of the formal economy by Rs 13 lakh crore. The flip side of this is that the size of the informal economy, for good or bad reasons, shrunk and now accounts for less than a fifth of the country’s national income—five years ago its share was over 50%.

Second, this formalisation is spreading gains to the rest of the economy, who were largely bypassed so far. Improved access to basics like electricity, housing, banking and so on, has only strengthened this process.

Clearly, formalisation of the economy is accelerating the ongoing makeover of the Indian economy.

Food for thought.

Recommended Viewing/Reading

Sharing the latest post of Capital Calculus on StratNews Global.

I followed up on last week’s newsletter, which drew from the recent paper published in the Harvard Business Review, flagging India’s growing importance as a consumer economy.

The paper co-authored by three professors asked a very blunt question: Do MNCs have an India strategy?

To explore this hypothesis, I spoke to one of the co-authors. Anup Srivastava, is professor at the University of Calgary.

Sharing the link below. Do watch and share your thoughts.

Also sharing my latest column in the Economic Times.

This time I took up from the theme I touched upon in a previous newsletter about the new public policy challenge posed by growing inequality in India.

Sharing the screenshot below. Do read and share your feedback.

Till we meet again next week, stay safe.

Dear Anil,

Excellent article! A large informal sector is a sign of underdevelopment.At present in India only around 10 % of workers are employed in the formal sector. Informal setor workers are employed in agriculture as well as non farm sectors. Their contribution to GDP is decreasing over the years.A structural transformation is required in India to shift the workers from informal to formal sector.

Demonetisation, GST, digital payments and enrollment of informal sector workers in government portals like e-Shrams have helped in formalisation of the economy and increasing the tax base. Formalisation leads to more tax revenue to the government and provides social security benefits to workers, enforcement of minimum wages, implementation of labour laws and proper documentation. Hence , if India has to become a super power, it cannot neglect these workers,!!

As always an excellent Article ! However there is still an archaic mindset in the bureaucracy at least towards the corporate tax payers. The latter is trying its best to scuffle the faceless assessments as an example.There are some pending Appellate cases going back a decade ! If further simplification is brought in, together with a changed mindset - the positive impact of that is anybody's guess !