The Q2GDP Shocker

Is the sharp deceleration in India's growth a one-off episode or is it structural in nature suggesting the beginning of a sustained slowdown? EPISODE #205

Dear Reader,

A very happy Monday to you.

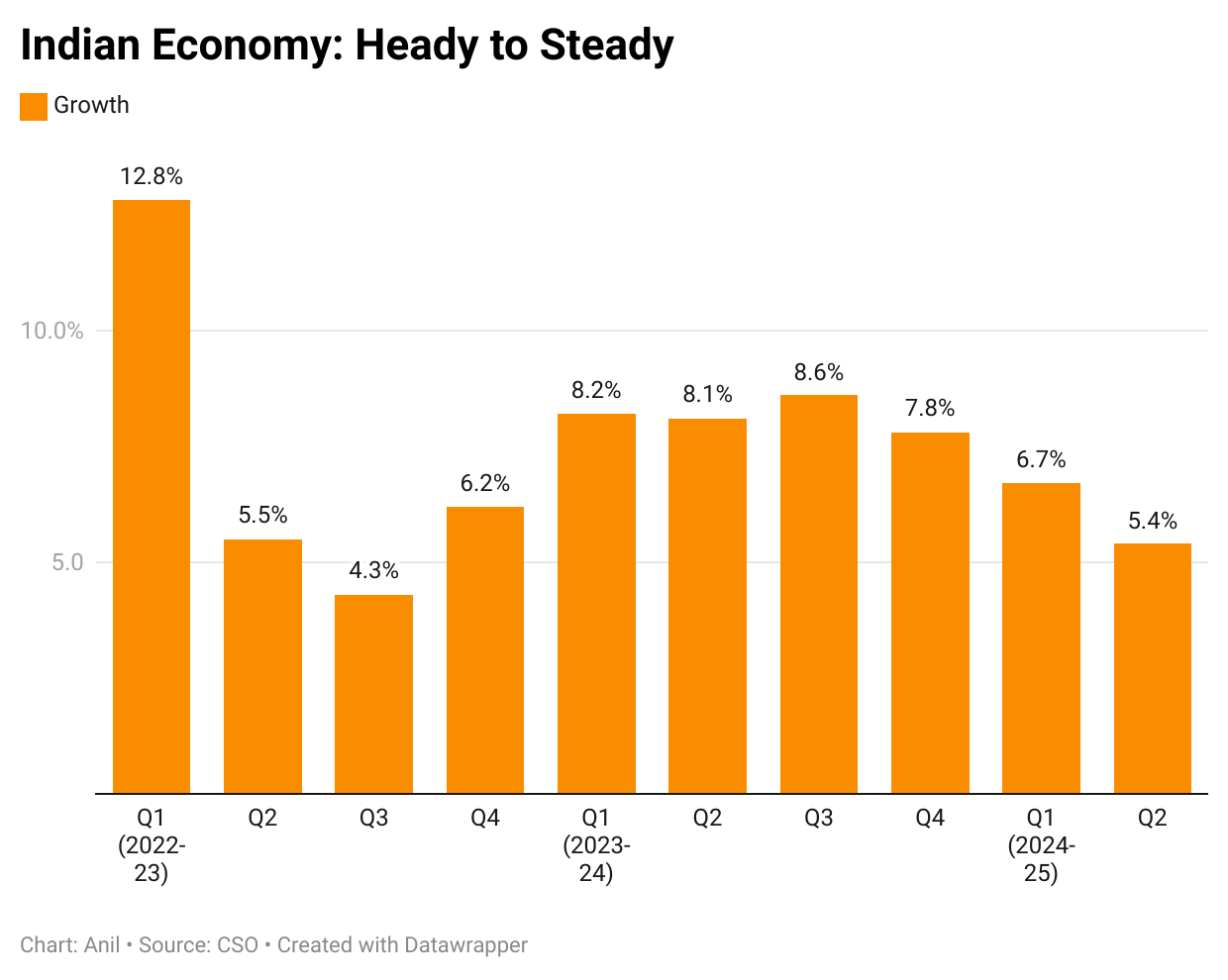

Last week the Central Statistical Office (CSO) shared the latest numbers on the Indian economy. It was a shocker: growth in the second quarter of 2024-25 ended September came in at 5.4%—substantially below the expected 7% and also the lowest in seven quarters.

The obvious question is whether this is a cyclical slowdown, which can be overcome by some corrective measures? Or is it a structural slowdown, suggesting that the Indian economy is seeing the beginning of a secular deceleration in growth? This week, I will unpack this worrying question.

Happy reading.

Growth Blues

Last week the Central Statistical Office (CSO), the official gatekeeper of India’s economic data, released the country’s latest growth numbers. It surprised on the downside. Dramatically at that. Growth in the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) was estimated at 5.4% in the second quarter ended September of 2024-25.

A cursory look at the above graphic which tracks quarterly growth rates will reveal two trends:

There is a secular loss in the growth momentum witnessed in the last two years;

And, this is the lowest growth rate in seven quarters.

So what conclusions do we draw? Is it cyclical or one-off? Or is it structural in nature, wherein the economy has encountered some chronic challenge, and hence the beginning of a secular slowdown?

My bet is on the first surmise.

Heady to Steady

Based on a host of reasons, most analysts have been warning us that the growth momentum had begun to slow after the fourth quarter of 2023-24 ended March.

The onset of the general election, which put the brakes on spending by the union and state governments, and the hiccup in government formation, were contributory factors. Inclement global conditions, due to deteriorating geopolitics only added to the uncertainty and worsening risks.

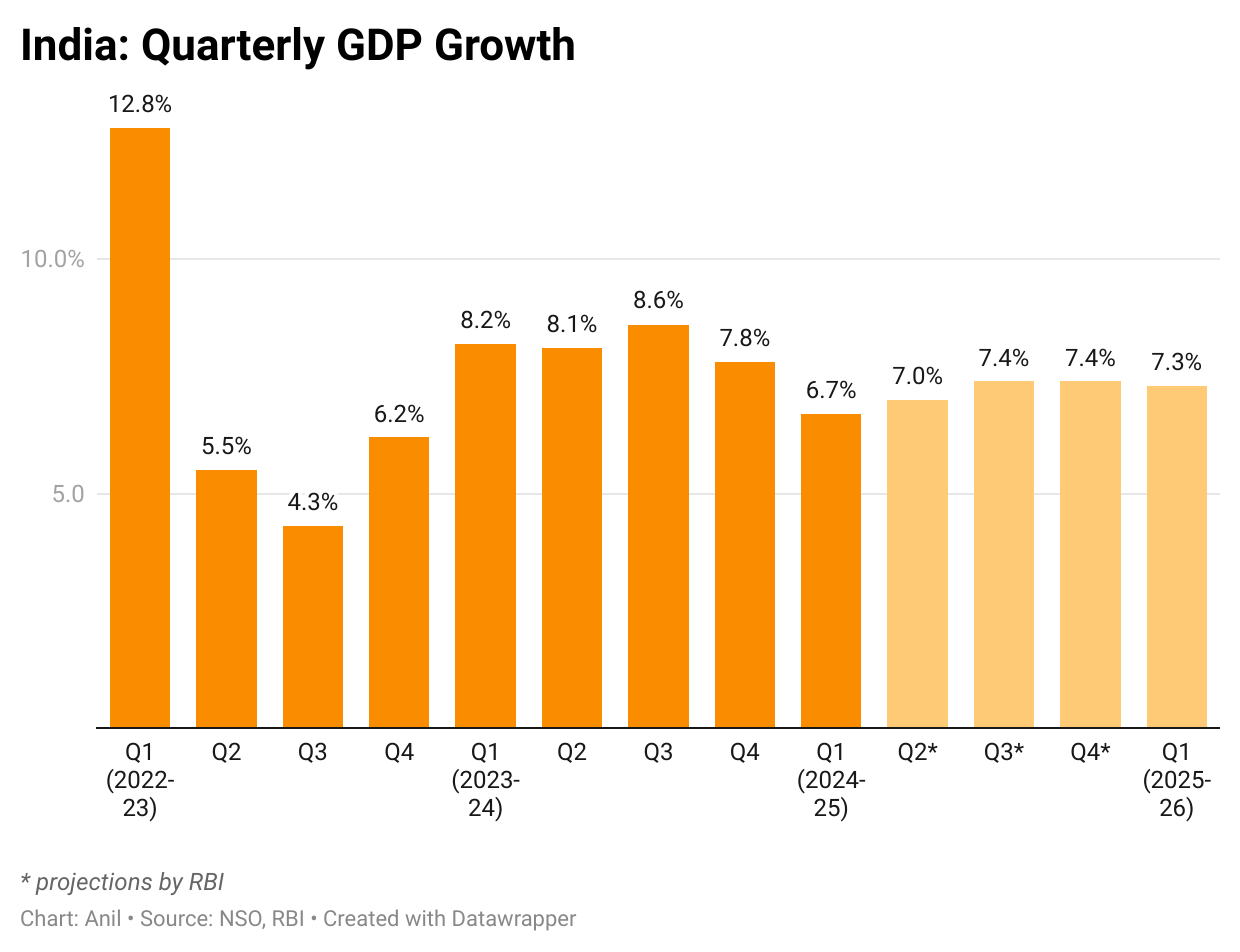

Unmindful of this, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) exuded confidence that the Indian economy will continue to defy cynics and that it was well on its way to clock a growth of 7.2% for 2024-25 and 7% for Q2 ended September—something we now know is way off the mark.

Similarly, the finance ministry projected a growth rate of 6.5-7% for the full fiscal year. In short, both North Block and Mint Street are bullish on the growth prospects of the Indian economy.

In fact, RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das went out on a limb and said:

“The NSO has placed India’s GDP growth at 6.7% in Q1 of 2024-25.

Notwithstanding the moderation in growth from the previous quarter and below our projection for Q1, the data shows that the fundamental growth drivers are gaining momentum.

This gives us confidence to say that the Indian growth story remains intact.”

The graphic shared above includes the optimistic projections by the RBI for the last three quarters of 2024-25. After the Q2GDP shock, these growth projections look a tad optimistic. India will have to grow exceptionally in the second half of the year, unless the provisional data for the previous half is revised upwards.

Worrying though these numbers are, it will be completely off the mark to ring the alarm bells on India’s remarkable growth story. For one, our expectations of the Indian economy have been raised, especially given its demonstration of unprecedented resilience in recent years.

Not only did it hold its own in the face of unprecedented back-to-back economic shocks beginning with the covid-19 pandemic, but the economy rebounded to become the fastest growing major economy in the world. In fact, the Indian economy clocked a very impressive 8.2% growth in 2023-24.

With the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that this heady rate of growth was an outlier and the outcome of a rare convergence of circumstances, including a round of structural economic reforms. At this stage—with the recent deceleration in growth momentum—it looks like the Indian economy is normalising, pivoting from a heady to a steady and more sustainable rate of growth.

Pranjul Bhandari, chief economist (India and Indonesia) for HSBC Ltd, summed it up best in a recent analyst note. After tracking 100 economic indicators, Pranjul’s note, put out a few weeks ago, said:

“We believe the growth exuberance over the past few years was led by the rise of several high-tech sectors (‘New India’). The exuberance in electronics manufacturing, Global Capability Centres, and digital start-ups, led to high growth and incomes at the top of the pyramid.

But after a few heady years, the base is rising, and growth in these sectors is normalising to more sustainable levels.

Overall GDP growth is gradually converging from 7%+ levels to a more sustainable but still strong ‘potential-growth’ level of around 6.5%.

If the improved prospects for agriculture stick, this new growth clip could be more equitably spread.”

Further, we should keep in mind that even a 6% growth is very impressive, especially for an economy which has now expanded to $3.7 trillion. Ideally, India should grow faster.

Reality Check

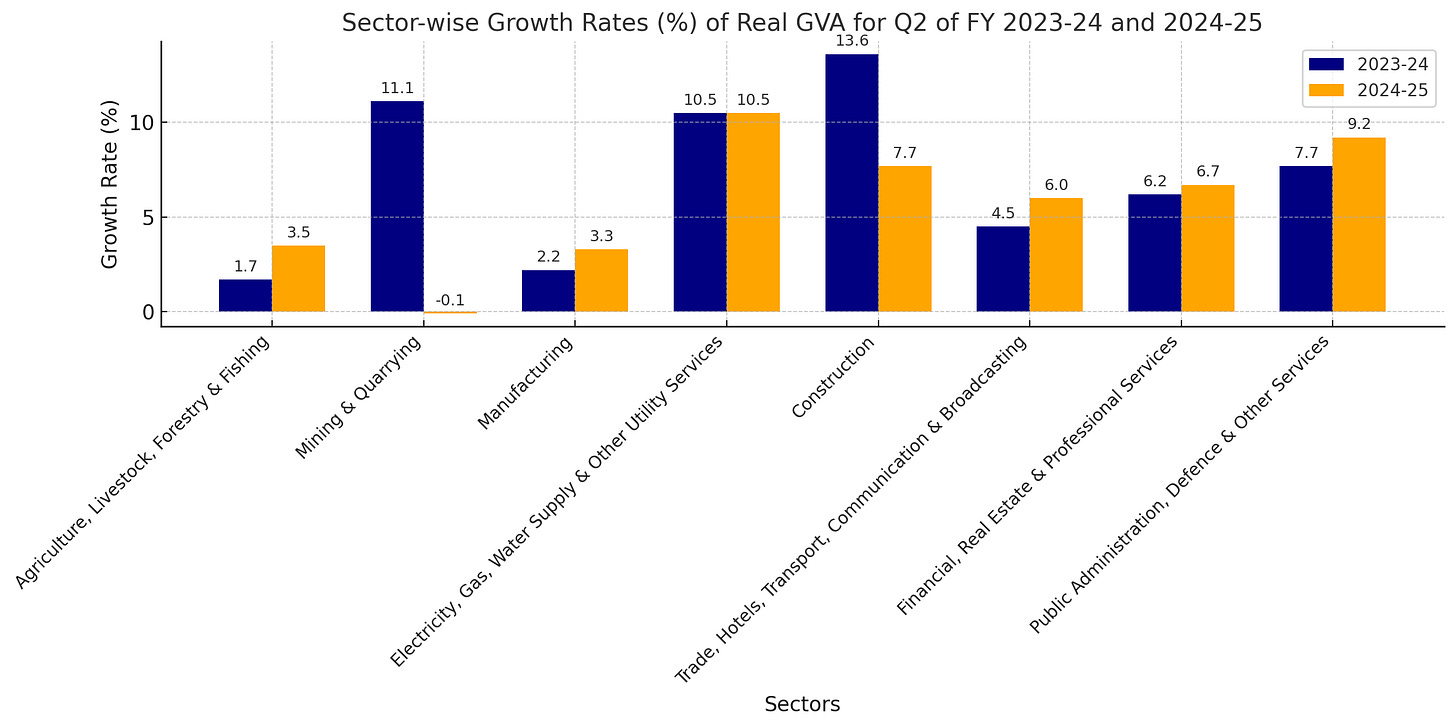

The Q2GDP data reveals that the sharp slowdown was triggered by a few sectors. While mining and quarrying contracted by 0.1%, construction slowed to 7.7% and manufacturing grew rather tepidly by 3.3%.

To be sure, this view is from the output side. GDP or output of the economy is measured as a sum of consumption and investment—which makes up the demand side of the equation.

The real story emerges when we look at this demand side of the GDP equation, especially investment levels. In the last five years, the acceleration in growth has been triggered and sustained by a surge in investment—accruing from the government and not the private sector.

With the government preoccupied by general elections, investment demand dipped. The private sector, which has been cooling its heels since the 2008 global financial crisis, failed to pick up the slack. Growth in investment decelerated from 7.5% in Q1 to 5.4% in Q2. Presumably, with electoral headaches out of the way, the government will put the focus back on rolling out its laudable investment target of Rs11 trillion for the current fiscal year.

On the other hand, consumption levels in the Indian economy have always posed a problem. The devastating fallout of the covid-19 pandemic and subsequent second, third round impact of other economic shocks has shrunk the purchasing power across the board. In fact, but for the massive step-up in welfare programmes—free food grains in particular—India would be facing a crisis of unprecedented proportions. Not surprising then, the share of consumption in GDP declined from 58.1% in 2021-22 to 55.8% in 2023-24.

The good news is that rural demand—buoyed by good monsoons and a cyclical upswing—is on the mend. Unfortunately, urban demand, which had been the backbone of consumption, is visibly in trouble.

As we approach the tail-end of this fiscal year, it is clear that the Indian economy is facing macroeconomic headwinds. Mercifully, they seem to be cyclical in nature and not structural. In other words, a quick policy correction can fix the problem.

It is also the time when the country’s finance minister sits down to ready for next year’s Union Budget due on 1 February. The tailwind of the unprecedented growth momentum witnessed in 2023-24 is not there. Growth is clearly pivoting from heady to a steady rate of growth and will require a recalibration of the policy mix.

A lot will also depend on RBI’s stance as it readies for its monetary policy review later this week: Will it signal a rollback of interest rate cuts?

Clearly, the spotlight is now on India’s macro economy. As they say watch this space.

Recommended Viewing

Sharing the latest episode of Capital Calculus.

Just like Mumbai has a moniker, Maximum City, Delhi too will have one of its own—Pollution City—if its annual tryst with pollution is not reversed.

According to the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), the number of days with poor air quality, wherein the Air Quality Index (AQI) is higher than 300, has progressively worsened in the last three years in Delhi.

Between October and February, the number of bad air quality days was 67 in 2021-22, 73 in 2022-23 and 92 in 2023-24. In other words, citizens of the national capital are overcome by hazardous pollution for three out of of the five months of winter!

To unpack the vexing nature of the pollution challenge and possible solutions, I spoke to Sachchida Nand (Sachi) Tripathi, Professor, IIT-Kanpur.

If you wish to come upto speed on the challenge of pollution, then this conversation with a domain expert like Prof Tripathi is unmissable. Sharing the link below:

Till we meet again next week, stay safe.

Thank You!

Finally, a big shoutout to Gautam and Premasundaran for your informed responses, kind appreciation and amplification of last week’s column and to Sumod for flagging an error. Once again, grateful for the conversation initiated by all readers. Gratitude to all those who responded on Twitter (X) and Linkedin.

Unfortunately, Twitter has disabled amplification of Substack links—perils of social media monopolies operating in a walled garden framework. I will be grateful therefore if you could spread the word. Nothing to beat the word of mouth.

Reader participation and amplification is key to growing this newsletter community. And, many thanks to readers who hit the like button😊.