THE INDIAN MONSOON'S NEW NORMAL

The nature and composition of the annual Monsoon phenomenon is undergoing a makeover causing a profound impact. EPISODE #42

Dear Reader,

A very happy Monday to you.

Sometime in the early 1990s I stumbled upon Alexander Frater’s book, Chasing the Monsoon. It is a fantastic account of the Indian Monsoon from the time it makes landfall in Kerala. Since then this life inducing spectacle has continued to fascinate me. It is another matter that it is also a key part of the work timeline of an economic journalist.

On my return to India after a six-year break on an assignment abroad, I was struck by a distinct change in the Monsoon. Anecdotally it seemed that the Monsoon was arriving a trifle late and was late in departing; it was like the Monsoon was shifting out by a few weeks. I recall flagging this to our Science correspondent who promptly dismissed the suggestion. I let it rest till the same reporter reverted some years later with what he claimed to be a scoop: the Monsoon was displaying structural changes. “Aha!” was my response, even as the reporter claimed selective amnesia.

This comical interlude aside, the larger point is that the Monsoon phenomenon is undergoing a change. Together with rapid urbanisation and infrastructure development this is making parts of India vulnerable to disasters. It goes without saying that the business of agriculture, something that is very dependent on the Monsoons in most parts of India, has become that much more unpredictable. Accordingly this week I put the spotlight on the ‘New Normal’ of the Indian Monsoon.

This week’s picture is a file picture taken by Satyan Chawla on Varandha Ghat Road in Maharashtra during the Monsoon.

A big shoutout to Gautam, Abhijit, Premasundaran, Vandana, Rahul and Aashish for your informed responses, appreciation and amplification. Gratitude also to all those who responded on Twitter. Reader participation and amplification is key to growing this newsletter community. And, many thanks to readers who hit the like button 😊.

If you are not already a subscriber, please do sign up and spread the word.

THE MONSOON MYSTERY

In a week from now the Monsoon will begin withdrawing from the sub-continent. At least that is the forecast of the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD).

At this stage it looks as though the IMD got its initial forecast spot on. In its first Long Range (LR) forecast issued on 16 April it projected normal rainfall at 98% of the Long Period Average (LPA) with a model error of ± 5%. The average seasonal rainfall for India during the Monsoon in the period 1961-2010 is 88 cm. The cumulative rainfall for the entire season beginning 1 June till 26 September (latest) is 86.49 cm—just 2% below the long term average.

One couldn’t be more precise.

Regional Disparities

But this is the headline number capturing total rainfall across the country. It actually hides more than it reveals, especially for a country like India with such contrasting topography.

A perusal of the regional rainfall data reveals large tracts are in deficit—made good by surplus rains in other parts of the country. And this seems to be the trend over the last few years; something most of us missed, because in nature change is always incremental, like an incoming tide almost invisible—one is aware of it only after it has come in.

In fact, the colour coded map of the cumulative rainfall for this season issued by the IMD is revealing. The first picture is the cumulative rainfall for this year and its distribution across the country as on 26 September:

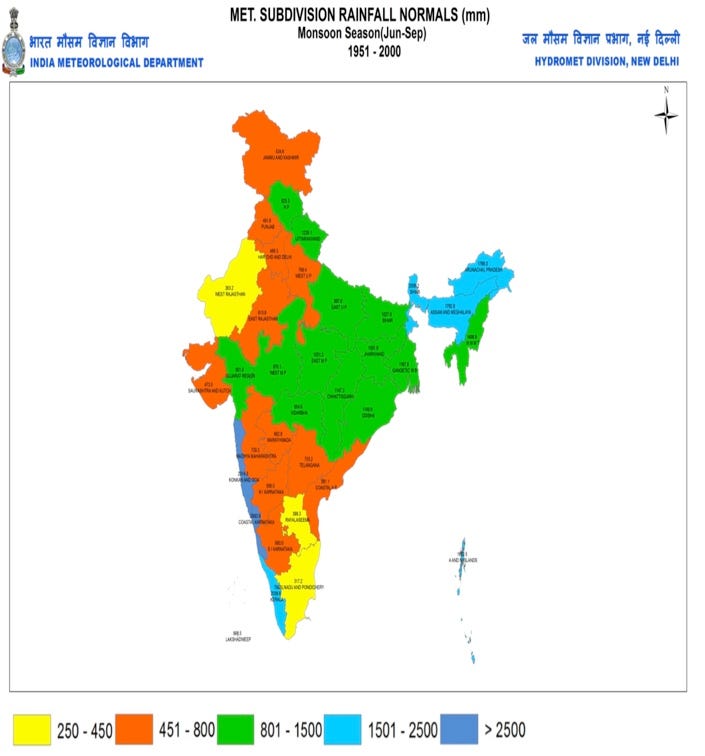

And the second image (apologies for the elongated shape of India. Unfortunately that is how IMD posted it online) is that of the average rainfall distribution of the Monsoon over 50 years ended 2000.

Even a cursory glance reveals how traditionally surplus regions, Kerala and the North-East, are now progressively receiving less rainfall. In fact, the North East is now in deficit, while Kerala just about reports normal rainfall. To be sure this is a comparison of the average against the actual of one year’s rainfall. While we can infer trends it is not wise to make specific conclusions. The big takeaway is that there is a new regional variation in rainfall.

Extreme Weather

Three years ago Kerala witnessed its worst flood in 100 years, displacing an estimating 1 million people and causing unprecedented devastation. The trigger was excess rains, 250% of the normal. Given the rapid urbanisation—one in two people live in urban areas—and deforestation, the impact of extreme weather was not surprising. The worry is that this is not a one-off tragedy.

To cite a few, there was the cloudburst in 2010 over Leh, causing immense damage and of course loss of life. Then in 2013, Odisha, always vulnerable to cyclones, was struck by the ferocious Phailin storm; in the same year the Chaurabari lake spilled over and inundated Kedarnath (miraculously, the shrine escaped serious damage). And then there was the disaster that struck Kashmir in 2014 when the Jhelum river overflowed, all but drowning Srinagar.

In the case of Kerala part of the reason is that the nature of the Monsoon has changed. It is no longer evenly distributed. Worse the bouts of rain are fewer but extremely intense. For various reasons, including encroachments and poor governance of urban settlements, the infrastructure is incapable of evacuating such surge in water loads—the result is flooding.

The bad news is that the frequency of extreme weather is only increasing. Data compiled by the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, instances of extreme weather have gone up five-fold from 71 in the 1970s to 350 in the first decade of the Millennium.

Mindset Reset

A complex system like the Monsoon needs a much more detailed explanation than what I have provided. My limited point is that it is time to revisit the idea of the Monsoon to understand the changes. In short we need new tools and ideas to try and understand a natural phenomenon of the Monsoon.

During my research for this column I stumbled upon the work of Sulochana Gadgil, an extremely accomplished Indian meteorologist. (I am enclosing a must read bio of Gadgil here.) Her ideas backed by peer vetted research makes a strong case for revisiting the accepted wisdom on the Indian Monsoon.

According to her conventional wisdom has it that the Monsoon is a very special system and arises because of land, sea contrast. Instead Gadgil proposes that the system is not special, but the fact that the phenomenon comes over the heated continent is special. The amplitude of seasonal variation is larger due to variations in sea-surface temperatures (SST).

To quote Gadgil from her bio:

“Variability of the monsoon is linked to that of cloud systems over the equatorial Indian Ocean. It may be possible to use this link to enhance the skill of monsoon predictions.”

Excited by her contrarian claim I stepped up research on her work and came across this podcast in which she lays out her arguments in detail. Those interested in listening to it can click here; but be warned that it is long and geeky—but if you read the bio and then listen to the podcast even a lay person like me could comprehend the wisdom of her claim.

According to Gadgil, climate change activists have long argued wrongly that the land will get hotter and hence the Monsoon will strengthen. The former claim is right, but the inference is wrong is what Gadgil says as the Monsoon is an outcome of SST. Studying data, Gadgil compiled a cloudiness index and diagnosed the SST threshold enabling formation and variability of convective clouds over the Indian Ocean, Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal.

So the Monsoon is not an outcome of a heating land mass—something we all grew up learning—but because of the SST reaching a particular threshold, is what Gadgil concludes. Viewing it in this way helps understand the variability of the Monsoon and thereby deploy mitigation measures.

In her view, to cite an example of mitigation, the existing agricultural practices are a hand me down from ancestors who evolved the crop mix by trial and error. However, beginning from the 1960s, both the seeds and varieties of crops have changed and experience is no longer a hand me down.

Worse agricultural scientists, according to Gadgil, refused to acknowledge climate as a variable influencing crop yield and output; instead they obsessed with fertilisers and chemicals. When they finally did relent they accepted climate change but rejected annual climate variability, she added.

I am no domain expert to second guess the claims of Gadgil. But what strikes me is that her innate academic instinct is suggesting we revisit the accepted paradigms—like we are doing with so many other issues around social policy in India. This is a small ask, especially as we need out of the box thinking to first accept that the Monsoon is undergoing a structural shift—achieving a ‘New Normal’ as it were—and then evolve mitigation strategies.

It is a long haul from there to figure cause and effect. Yet a good place to start introspection.

Recommended Viewing

Sticking to the theme of the Indian Monsoon I dug out this documentary version of the idea behind Frater’s book by Sturla Gunnarsson.

In their own words:

“A cinematic journey into the terrain where nature, science, belief and wonder converge in one of the most astonishing and breathtaking landscapes on earth, Monsoon is a film that captures the timelessness and rich human drama of our engagement with the natural world.”

Sharing the trailer:

If you liked the trailer and would like to watch the entire documentary then here goes:

Till we meet again next week. Stay safe.

Dear Anil,

An excellant article on significance and contribution of environment to economic development .The rising population of developing countries and the affluent consumption and production standards of developed world have placed a huge stress on enviornment. Many resources have become extinct and the wastes generated are beyond the absorptive capacity of the earth.The industrial development has polluted and dried up rivers and other water bodies making water an economic good.

The developmental activities in India have resulted in pressure on its natural resources. Air pollution , water contamination, soil erosion,deforestation, changes in monsoon pattern , wildlife extinction are some of the most pressing environmental concerns of India.India supports around 17 % of worlds population and 20% of livestock population on a mere 2.5% of worlds geographical area. Global Warming and depletion of ozone layer are the challenges which need to be tackled at a global level to attain the Sustainable Development goals.

Satyen Chawla has captured the raw beauty of Varandha Ghats beautifully .

Anil, that was a great article. I deal with climate change, environment, sustainability & related stuff, and found the science behind the research you did extremely relevant. You are so right; it's the spatial and temporal variations that make the heterogeneity in the distribution and patterns of precipitation so disruptive for the economy at large. The increasing frequency of the "extreme climate events" (yes, that's the terminology used by the scientists) ought to have made the policy makers more proactive than what it is. But these things are never easy; so, fingers crossed !