Kerala's Fiscal Outrage

Kerala's face off with the Centre flags the need to balance fiscal decentralisation with macroeconomic stability and responsibility. EPISODE #171

Dear Reader,

A very happy Monday to you.

Last week the Supreme Court rejected Kerala’s appeal to prevail upon the union government to relax the annual cap imposed on its borrowings.

Worryingly, the centre-state fiscal dispute—flowing from Article 293 (3) of the Constitution which requires states to obtain the centre’s consent to borrow from the market—has been kept alive though, with the matter referred to a Constitution Bench.

Frankly, there is a larger message implicit in this dispute. It is about striking the right balance between growing fiscal decentralisation and macroeconomic stability and responsibility—basically neither the union nor the states can go off on a tangent with their borrowing plans and instead have to operate within fiscal guardrails.

Essentially, this is uncharted territory and is defining new contours for cooperative federalism—ideally courts should steer clear and leave it to elected representatives. This week I try and unpack this thought.

The cover picture is a striking random street view from Goa. The shop hoarding is an oxymoron indeed.

Happy reading.

Cooperative Federalism

Last week the Supreme Court of India declined Kerala’s request to prevail upon the centre to relax the cap imposed on their annual borrowings. The state which is staring at an unprecedented financial crisis is desperate for extra funds—even if they accrue as borrowings and add to their future debt burden.

Given that it is general election season and the fact that the Left Democratic Front (LDF)-ruled Kerala is politically opposed to the ruling Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP)-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) at the centre has given the entire dispute a political hue.

While the state believes that it has the right to borrow, the centre says it has to be within limits—defined by standard fiscal parameters. However, it is not such a simple binary.

The matter is nuanced and needs calmer heads, especially since it determines the emerging contours of cooperative federalism—something that gave us the Goods and Services Tax (GST), which for the first time economically unified the country— and thereby the collective fiscal future of India.

Kerala, which is staring at a financial crisis, is right in seeking relief. The question is the means to the end—borrowings when your finances are in red is only worsening the problem.

The centre is equally right in arguing for fiscal probity—and to be fair to them, they have been walking the talk. The centre is insisting that borrowings cannot breach the fiscal guard rails. They are right. All it requires is one bad egg, to trigger a national financial crisis.

A solution requires a bail-out with a blueprint for reclaiming fiscal stability. Both sides have to blink. It is for national good and hence cannot stem from an an adversarial view.

At the least, the courts should steer clear off this challenge and instead leave it to the elected representatives.

Haseeb Drabu, the former finance minister of Jammu and Kashmir and part of the founding team of FMs who rolled out GST, summed it up best in a recent conversation with me. Check out the quote below:

For the first time, Kerala has gone to the Supreme Court against the central government on borrowings. This is serious. Is the judiciary going to decide the fiscal policy of either the states or the centre? I am unable to wrap my head around this: Will the Supreme Court decide on borrowings which are based on fiscal parameters? I am not taking a view whether Kerala is entitled to breach the cap on borrowings. Instead, the simple fact of going to court itself is a very serious matter and this needs to be discussed.

—Haseeb Drabu, former Finance Minister of Jammu & Kashmir.

The Problem

The legal challenge arose because Kerala ran into a fiscal problem. Its dues on account of salaries and pensions far exceeded the capacity of its receipts—if it has to avoid default on its obligations, the state has no option other than additional borrowings.

The state’s finance minister K N Balagopal admitted as much in his speech delivered last year while presenting the budget for 2023-24. (The bold text is there in the original speech)

“If ₹46,754 crore was the required amount to disburse salary and pension during 2020-21, ₹71,393 crore was the required amount for 2021-22. Through this alone the Government has assumed an additional commitment of ₹24000 crore.”

In two years the liability of Kerala under the head of salaries and pension has grown by a staggering 52.6%. Worse, it wanted to bridge this shortfall through additional borrowings of Rs26,626 crore.

Upfront it is clear that the choice before Kerala entails a moral hazard. You can’t be borrowing to fund your revenue expenditure—tantamount to a household borrowing to fund its daily consumption needs. Prima facie, the situation smacks of financial mismanagement.

However, the state claims this is because they have been denied their due resources by the union government—a similar claim of ‘he-said, she-said’ is being made by other opposition ruled states. Even if the latter is true, then logically more states too should be staring at similar fiscal disaster. This is not the case.

Kerala also wanted the union government to walk back its decision to bring off-budget borrowings within the annual cap.

Once again, doing so would open the door to more states following suit, making mockery of the idea of a ceiling on borrowings—designed to ensure that too much of borrowings by the government, union and states, do not crowd out private debt demand and raise the cost of borrowings.

Besides demanding interim relief—consent to raise borrowings over and above the ceiling—it also questioned the right of the union government to impose such a cap on borrowings by states using Article 293 (3) of the Constitution.

Fiscal Decentralisation

The genesis of the problem is the decision to encourage fiscal decentralisation over the last two decades. Previously, the centre would extend loans to states. Now, states, if they so desired, are empowered to borrow on their own. Barring a few states, most opted for this route. The graphic above shows how gross market borrowings by states have grown dramatically. In seven years, it has nearly doubled to Rs 7.58 lakh crore in 2022-23.

Fiscal decentralisation is not a bad thing. For an economy that is rapidly pivoting to one based on the market economy, such iterations are par for the course. Only that like all freedoms, fiscal freedom too comes with responsibility.

As a precaution, the centre took care to put fiscal guardrails in place to ensure states did not go off on a fiscally irresponsible tangent. It amended the Fiscal Responsbility and Budget Management Act, 2003, in 2018 wherein the union government was authorised to ensure that together the debt of the centre and states did not exceed 60% of gross domestic product.

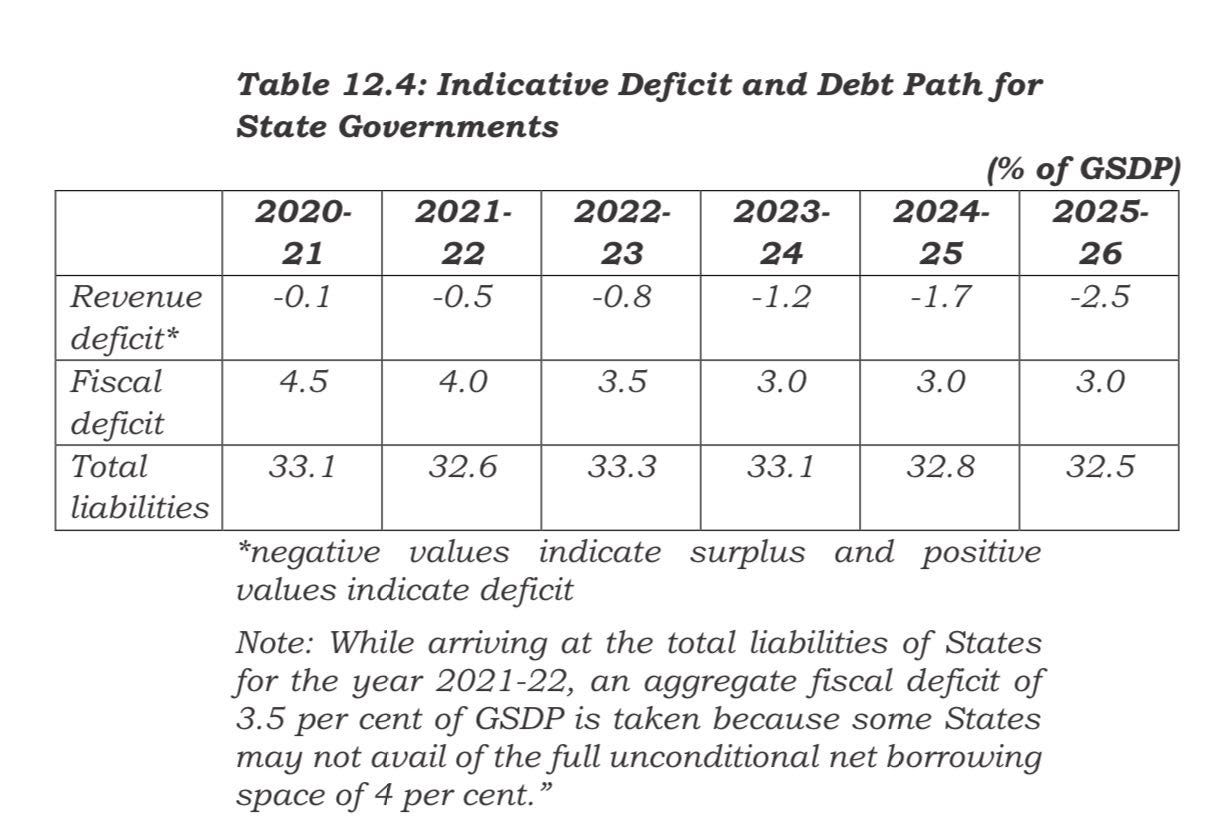

Accordingly, it drew up a debt path for state governments. Check the graphic below sourced from the Supreme Court order.

It is under this fiscal prudence plan that the centre imposed a cap on Kerala’s annual borrowings in March last year at 3% of GDP. And, this cap included off-budget borrowings (like using state-owned enterprises to raise borrowings).

To be fair to the union government, they cleaned up their act on this legacy practice of indulging in off-balance sheet borrowings two years ago. So it is walking the talk of its fiscal sermon. With the union government refusing to blink, the state decided to move the Supreme Court for relief.

The Verdict

The Supreme Court heard out both sides and eventually rejected Kerala’s demand for an interim relief. At the same time it nudged the union government into allowing the state to borrow an extra Rs 13,608 crore.

The good news of the order is that the apex court specifically flagged the importance of fiscal prudence. (The bold text is my doing.)

“There is an arguable point that if we were to issue interim mandatory injunction in such like cases, it might set a bad precedent in law that would enable the States to flout fiscal policies and still successfully claim additional borrowings.”

The bad news, in my view, is that they have opened the door on examining the contours of the fiscal arrangement—which is still evolving—between two elected institutions under Article 293 (3) of the Constitution of India.

Accordingly, it has proposed a Constitution bench of five judges under the leadership of the Chief Justice of India to examine a range of issues, including the following (the bold text is my doing):

Is fiscal decentralisation an aspect of Indian federalism? If yes, is the union government’s actions to maintain fiscal health violate the principles of federalism?

Is it mandatory for the union government to have prior consultations with the states for giving effect to the recommendations of the Finance Commission?

Keep in mind, Article 293 (3) of the Constitution has not been subject of many legal interpretations so far. While not preempting what the apex court may have to say on the matter, it would seem that it is meandering into the role and power of two democratically elected institutions—the centre and states.

In my view this is best left to the centre and states to resolve. They have shown stunning consensus in coming up with the idea of GST—the most powerful tax reform of modern India wherein the states and the union government sacrificed their respective sovereign powers for national good. It set the tone and template for cooperative federalism.

Further, in all such trade-offs—and India will see more of this as it goes forward—the decision has to be the will of the people. And, in a democracy like India, this is articulated through their elected representatives in government. It is only natural that there will be differences, especially when they are governed by rival political parties. GST showed us they can rise above politics.

As Abraham Lincoln said in his famous Gettysburg address, it is government of the people, by the people, and for the people.

In short people’s power is supreme. Respect it.

Recommended Viewing/Reading

Sharing the latest post of Capital Calculus on StratNews Global.

One of the worst kept secrets about rural India is that despite accounting for two-third’s of the country’s population and nearly half of its gross domestic product, their access to formal credit is less than 10%.

Part of the reason is that most of rural India till recently was unbanked. All this is changing though. In the last 10 years, 50 crore people have been banked. The spread of FinTech has enabled microfinance institutions to extend loans for improving livelihoods of women in low-income households. To unpack this trend I spoke to Sadaf Sayeed, CEO, Muthoot MicroFin—the third largest lender in South India.

The revelations were stunning. For example, microfinance institutions have extended small-ticket loans to nearly 8 crore individuals—effectively that many households—setting in motion a powerful socio-economic makeover.

Sharing the link below. Do watch and share your thoughts.

Till we meet again next week, stay safe.

Thank You!

Finally, a big shoutout to Shiv, Aashish, Shashwathi, Premasundaran and Ranjini for your informed responses, kind appreciation and amplification of last week’s column. Once again, grateful for the conversation initiated by all you readers. Gratitude also to all those who responded on Twitter and Linkedin.

Unfortunately, Twitter has disabled amplification of Substack links—perils of social media monopolies operating in a walled garden framework. I would be grateful therefore if you could spread the word. Nothing to beat the word of mouth.

Reader participation and amplification is key to growing this newsletter community. And, many thanks to readers who hit the like button😊.

This is indeed a serious issue affecting centre state relationship. Of course, we should expect SC to enlighten us with its own pearls of wisdom, though any wise counsel should be against it. Anyway, the main point is this- we must decide how much percentage of income from taxes and levies etc. should be utilised for cost of administration like salaries, pension etc. and follow the limits strictly. It should not be the case that taxes are used up almost entirely for salaries and pensions and such basic operating expenses!!! Finance Commission should be asked to develop such norms for the states and the centre. This should be in addition to the Fiscal Responsibility Act which covers extent of permissible borrowings. There is no politics here; just pure routine management of fiscal affairs.

Hi Anil, a wonderful article as always. Displays your journalistic prowess to an exponent. Warrants repeated readings!