India Votes

Democracy's biggest spectacle is poised to begin when little under a record one billion voters queue up to elect the next government. EPISODE #170

Dear Reader,

A very happy Monday to you.

Later this month the largest exercise in democracy will begin. Over the next two months, nearly one billion voters will decide on who will form the next government.

This week I try and unpack the enormity of this exercise. Like everything else about India, elections too are an exercise in scale. Putting this together is no mean task. This is indeed a tribute to India and a timely reminder about the importance of each vote.

The cover picture is this brilliant caricature of the ubiquitous queue in India by Mario. In some ways it is a metaphor for nearly one billion queueing up to cast their vote over the next two months. Enjoy.

Happy reading.

Dance of Democracy

Did you know that the first general election in India was held over 68 phases lasting about four months? It began on 25 October 1951 and ended on 21 February 1952.

Fast forward to this year’s election, in which voting begins on 19 April and concludes on 1 June—with the results being declared on 4 June. It has a staggering electoral list of nearly a billion voters (968 million to be precise)—more than twice the population of the United States, the world’s oldest democracy.

Further, did you know, that unlike the United States and England, the right to vote was always universal in India?

In fact, from the very first general election, the world’s largest democracy held out a lesson to the United States, the oldest democracy, and England, wherein the right to vote was limited by gender (women could not vote) and race (non-whites could not vote)—errors that were corrected relatively recently.

(Ironic then that the Western democracies who continue to struggle with paper ballots, never cease to lecture India on what they perceive to be flaws in its democratic credentials. Guess, another day, another story.)

Fascinatingly, the energy, enthusiasm is the same even decades after the country held its first general election. Indian democracy is alive, kicking and thriving. Check out an old video on the first general election I pulled from the archives of the Election Commission of India (ECI).

In short, India’s upcoming noisy dance of democracy is unprecedented. Its tryst with democracy has held up, despite threats from within (including the imposition of Emergency in 1975, resulting in two gap years in India’s democratic history) and outside.

Indeed it is a tribute to a nation that has denied so many doomsday prophecies. The most remarkable thing is that it is a constant work in progress—from introduction of Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs) to the recent rejig of the institutional structure of the ECI on the advice of the Supreme Court of India.

The Electoral Sherpa

In the run-up to this year’s general election the villagers of Dumak in Uttarakhand's Chamoli district threatened a boycott.

Unless of course the government fulfilled their demand for the construction of a road they had been demanding since the 1990s. The government blinked and has committed to a timeline to deliver on the road and the villagers have walked back their boycott.

This anecdote reminded me about a conversation I had long ago with a young bureaucrat who was doing duty as an election observer in Rajasthan. The bureaucrat shared a story similar to the one we saw playing out in Uttarakhand last week. Coincidentally, decades later this bureaucrat went on to join the ECI as a member. The person in question is Ashok Lavasa.

Ahead of the 1998 Lok Sabha election, Lavasa, the election observer for the Bayana Lok Sabha constituency in Rajasthan, discovered that one of the villages with 100 adults did not vote. A curious Lavasa journeyed to the village. It was an adventure as there was no road connecting the village to the main road. Instead, it was a mud pathway that he traversed with the help of a tractor.

The villagers when pressed said they had collectively boycotted elections in protest against the administration refusing to cater to their request for a road. Effectively, like their counterparts in Uttarakhand, they were casting a negative vote. I wrote about this in Mint many moons ago. Click this link if you wish to read it.

This anecdote is not about civil protest. Instead it is about bringing home the point that our electoral sherpas go to elaborate lengths to get people to exercise their democratic right.

Hence, I marvel at those among us who skip voting day to claim an extra holiday or the losing political parties who accuse the ECI of bias and rigging of elections. At the least, respect your vote if not the process and the institution.

Gender Parity

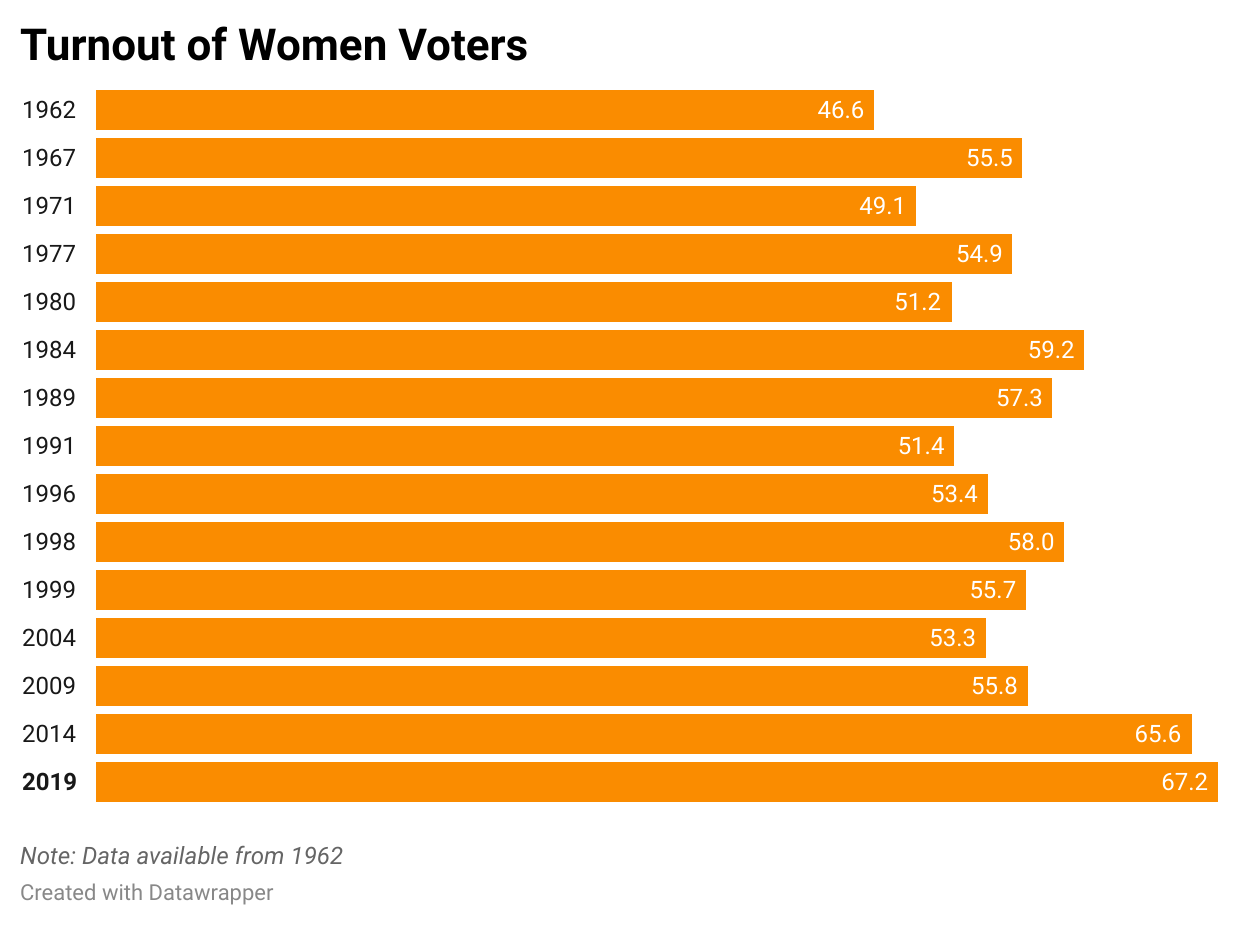

Another salutary feature has been the ability of the ECI to get out the women voter. In fact, for the first time ever, in 2019 the turnout of women voters topped that of men. Remember, in the third election—from which data is available—the turnout of men exceeded women voters by 16.7 percentage points.

It also explains why women have emerged as the most important cohort in recent elections—general election as well as those to state assemblies.

The recent securing of reservation for women in elected houses of both states and the centre through a law only reaffirms this. Sharing a previous newsletter I wrote about the significance of this move.

X-Factor Claims Centrestage

Dear Reader, A very Happy Monday to you. In 1996, the United Front government, a motley coalition of political parties, led by Deve Gowda proposed mandatory reservation for women in Parliament and legislatures. However, some of the constituents of the coalition were dead opposed to the idea. Supported by allies from outside, they successfully nixed the in…

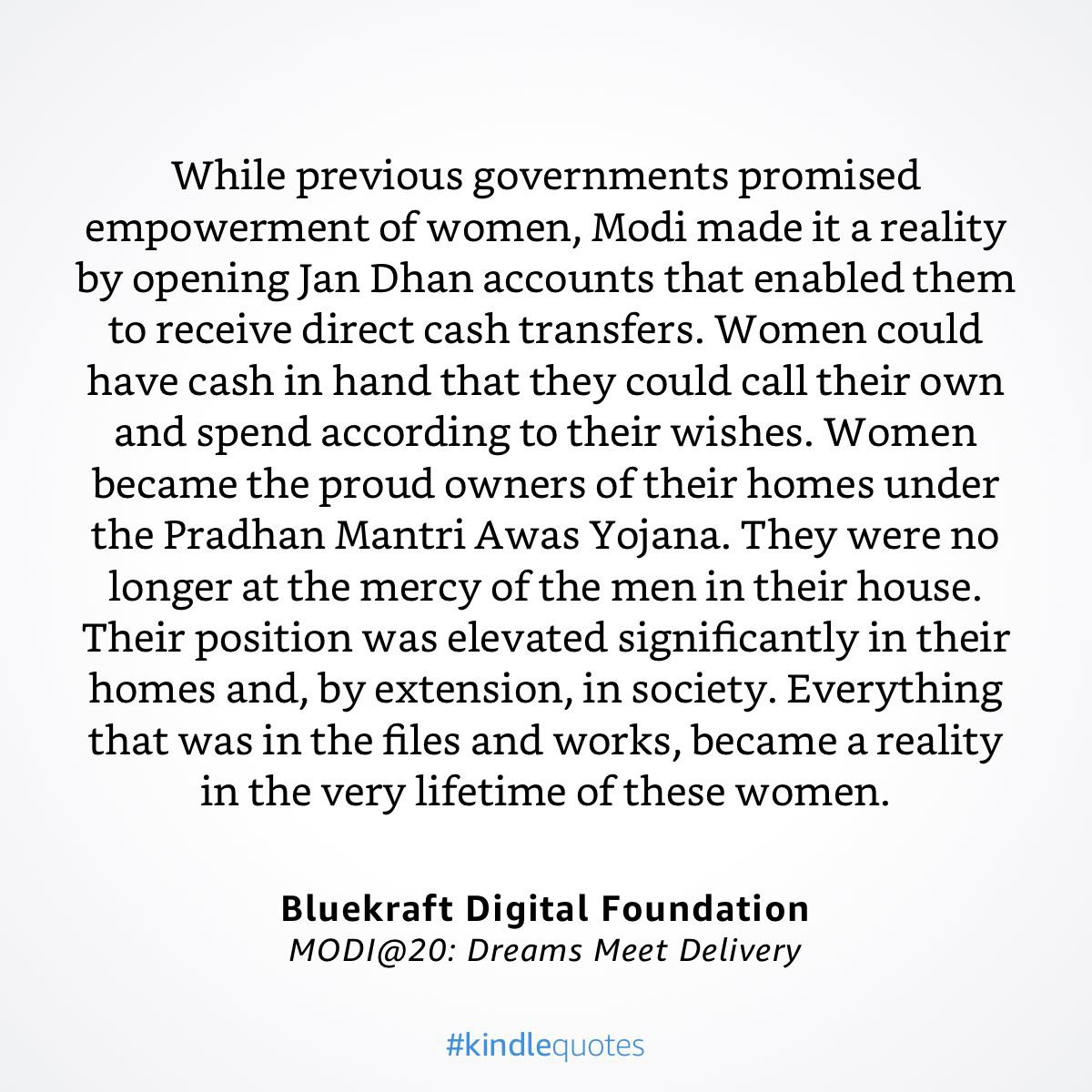

In this battle to gain support of women voters, undoubtedly the incumbent government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi holds the upper hand at the national level. Pradeep Gupta, the pollster with the golden arm in calling elections correctly, summed it up best in his contribution to a collection of articles on Modi’s two decades at the helm—first as chief minister of Gujarat and then as PM.

The Opposition however has been snapping at BJP’s heels. In the recent elections to the state assembly in Karnataka, the Congress struck a chord with women voters with the promise to address their pain points, especially with respect to rise in cooking gas prices, to pull off a landslide win.

Level Playing Field

The ECI’s biggest challenge is to ensure a modicum of a level playing field. Especially, given the fact that general elections in India involve big money—mostly unaccounted cash.

Check out the graphic above sourced from the ECI, which records the exponential growth in seizures of cash. Imagine, the sums that escaped scrutiny.

In fact, for those getting their knickers in a twist over the recent apex court verdict on electoral bonds, should remember: One, this was funding with an audit trail. Second, it is a mere fraction of the sums that go into financing elections.

Frankly, the apex court’s solution was a case of throwing the baby out with the bath water. Obviously, the scheme had flaws, which needed to be resolved. But, now we are back to merry old ways of electoral politics were cash is king, while the indignant among us feel assuaged.

I remember a private bank CEO telling me this gripping story about the travails of electoral contributions to a political party. The personnel that carried the cash were locked up in a room till such time (over a week) they wrote out equivalent donation slips for sums less than Rs20—below which political parties do not need to share the source of funding.

Future Bright

Reflecting India’s demographic bulge—wherein 65% are less than 35 years—the voter base too is growing at the bottom.

This year 1.8 crore first time voters will get their taste of democracy. Together with 19.74 crore voters in the age group of 20-29 years, the youth voter base of India is 21.54 crore—more than a fifth of total number of voters. (Check out the graphic above sourced from ECI.)

The Scale

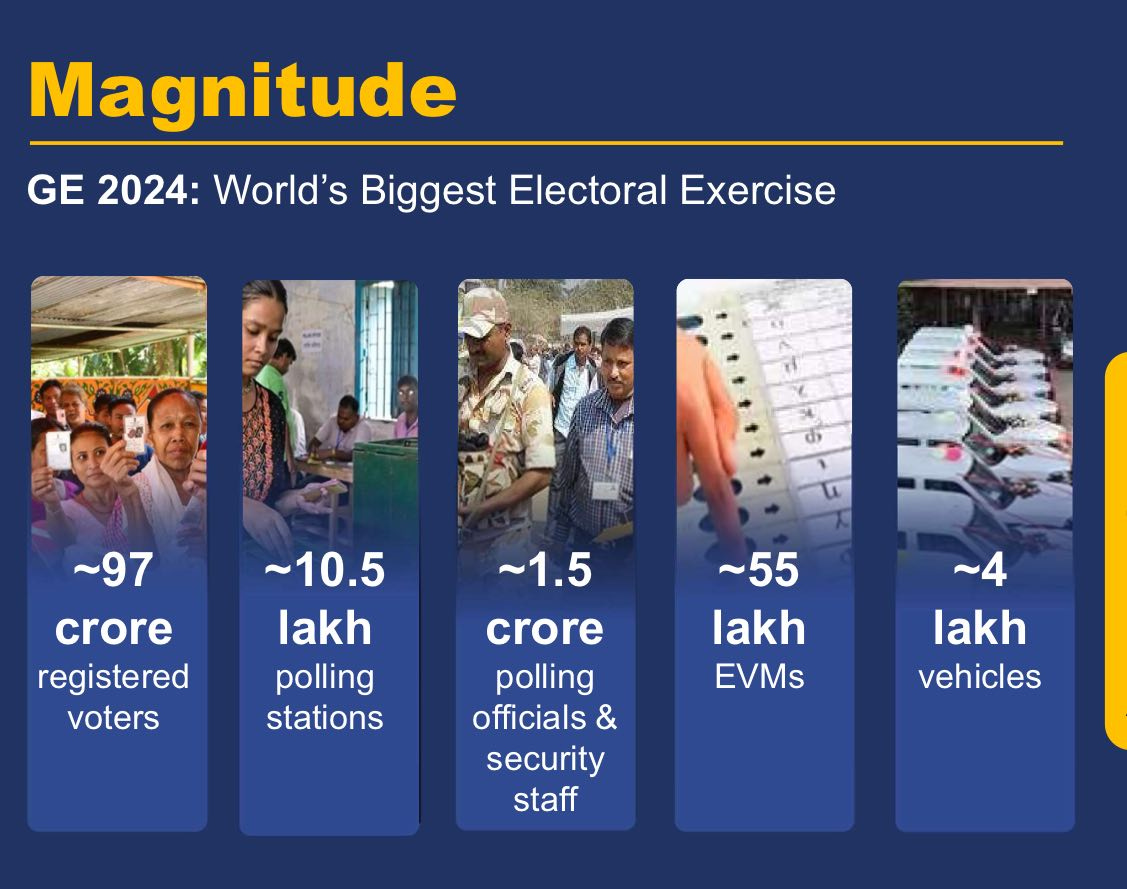

Like I said at the beginning, organising an election of this scale involves unbelievable logistics. Check out the graphic above.

The election infrastructure involves:

10.5 lakh polling stations

1.5 crore polling officials and security staff

55 lakh EVMs

4 lakh vehicles

If you were of my vintage you would recall instances of booth capture, violence and scores of re-polls. All of this has reduced significantly. It is still a work in progress though. Not a write-off as suggested in some quarters. Instead, Indian democracy is very much alive and thriving.

Recommended Viewing/Reading

Sharing the latest post of Capital Calculus on StratNews Global.

Last week I shared a sneak peek to my conversation with Haseeb Drabu. I took up where I left off in the newsletter examining the contrasting electoral guarantees of the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Congress.

In this very insightful and frank conversation, Haseeb drew the distinction between a welfare measure and a freebie—and the cost to the exchequer such reckless populism causes.

Sharing the link below. Do watch and share your thoughts.

Till we meet again next week, stay safe.

Thank You!

Finally, a big shoutout to Nimesh, Premasundaran and Ranjini for your informed responses, kind appreciation and amplification of last week’s column. Once again, grateful for the conversation initiated by all you readers. Gratitude also to all those who responded on Twitter and Linkedin.

Unfortunately, Twitter has disabled amplification of Substack links—perils of social media monopolies operating in a walled garden framework. I would be grateful therefore if you could spread the word. Nothing to beat the word of mouth.

Reader participation and amplification is key to growing this newsletter community. And, many thanks to readers who hit the like button😊.

Dear Anil

At the outset let me thank you for the old video on the first general election. A very rare footage and such a clear picture of how much things have changed for the better. Like you have rightly pointed out, everything in India is of mammoth proportions simply due to the huge numbers involved. When we used to read about the Covid vaccines we used to feel proud of the huge numbers to get vaccinated. Same with the number of gas connections, bank accounts, houses with running water and so on. The numbers are more than the population of most countries!

The election process is no different. The number of officials working round the clock to ensure a smooth running of the booths. The task of ensuring that people even in remote and inaccessible places get a chance to cast their votes. There is the postal ballot for personnel posted far away from their hometowns. All these have to be completed within the stipulated time frame.

We have a lot to be grateful for. Women didn't have to fight to get their voting rights. No one was alienated on the basis of skin colour. Even trials and others living in remote areas were not neglected. Plus, there is so much of progress in the process.

Let's just hope that people will cast their precious votes judiciously and not simply consider that date to enjoy a quiet holiday at home. Atleast we should get a good democratically elected government. We surely deserve that.

Hi Anil, great article! Thoroughly insightful.